More Than “Good-job”

Verbal Validation for Kids is More Than “Good-Job”

By: Sasha Pipke

Dopamine, also commonly referred to as the “feel-good” hormone is associated with motivation and reward-driven learning. Dopamine allows for a positive sensation released in the brain that motivates future actions, allowing for a similar release of the hormone (Bogacz, 2020). Children continuously use dopamine to further build connections and reinforce habits within their brains. Parents, teachers, aides, and therapists consistently reward children with positive words of affirmation to reinforce positive behaviour in their developing minds. This motivation is known as extrinsic motivation, where the child receives external validation and praise, as opposed to intrinsic motivation (which involves of self-encouragement). The choice of words used by adults plays a critical role in the child’s motivation. We often resort to saying “good job” to further validate the actions of others, yet this phrase is an overgeneralized blanket term, used regardless of the task at hand. Although this seems like the perfect phrase to continue to motivate the child to perform a task, it lacks meaning and does not specifically recognize accomplishments. We must ask ourselves, therefore, how can we change our vocabulary to motivate children in a meaningful way?

As we know, “good job” is ambiguous and vague, so to create a more profound and meaningful outcome it can be helpful to describe what you see or hear. When children understand what they are receiving praise for, motivation to complete the task again or similar tasks with the same effort increases (Schwarz,2018). It’s important to still use vocabulary that the child understands and can easily understand in a positive context. Some examples are:

- “Wow, I love how you rounded your lips to make your quiet (/sh/) sound!”

- “You washed your hands all by yourself, nice work!”

- “Thank you for using your ears and turning off the TV when I asked!”

Additionally, it is important to provide children with the success of their actions. This allows you to provide extrinsic motivation in a way that will allow your child to also feel intrinsic motivation. This can be done with personalized ‘you’ statements that place ownership on the child for their own actions. Some examples are:

- “You were very kind sharing your game with your brother, it made him very happy.”

- “I’m very proud of you for tying your shoes all by yourself!”

- “You worked so hard today sounding out your words, you are very smart!”

Lastly, it is important to highlight the effort, especially in situations where the end goal was not reached. When you emphasize the effort, it allows for a transition of mindset within the child; rather than thinking of something as a failure, it becomes motivation to continue to try and succeed later. Goals do not happen overnight, and children should not expect that everything they do will be accomplished at the same rate.

Saying “good job” has become hardwired to address success in children, however, it does not carry substantial meaning. Changing our vocabulary to better highlight children’s effort and success is a small change that can make the word of difference regarding self-praise and motivation. This change in vocabulary will not happen immediately. Try to first notice in a week how many times you say “good job” then try to replace a few “good jobs” with a specific validating phrase and continue to progress from there. You’ve got this!

References

Bogacz, R.(2020). Dopamine role in learning and action inference. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.53262.

Corinne. (2019). Why You Should Stop Saying Good Job and What to Say Instead. The Pragmatic Parent. https://www.thepragmaticparent.com/stopsayinggoodjob/.

Schwarz, N. (2018). 50 Ways to Say “Good Job” (Without Saying “Good Job”). Imperfect Families. https://imperfectfamilies.com/50-ways-to-say-good-job-without-saying-good-job/#:~:text=Author%20Alfie%20Kohn%20talks%20about,reduce%20their%20sense%20of%20achievement.

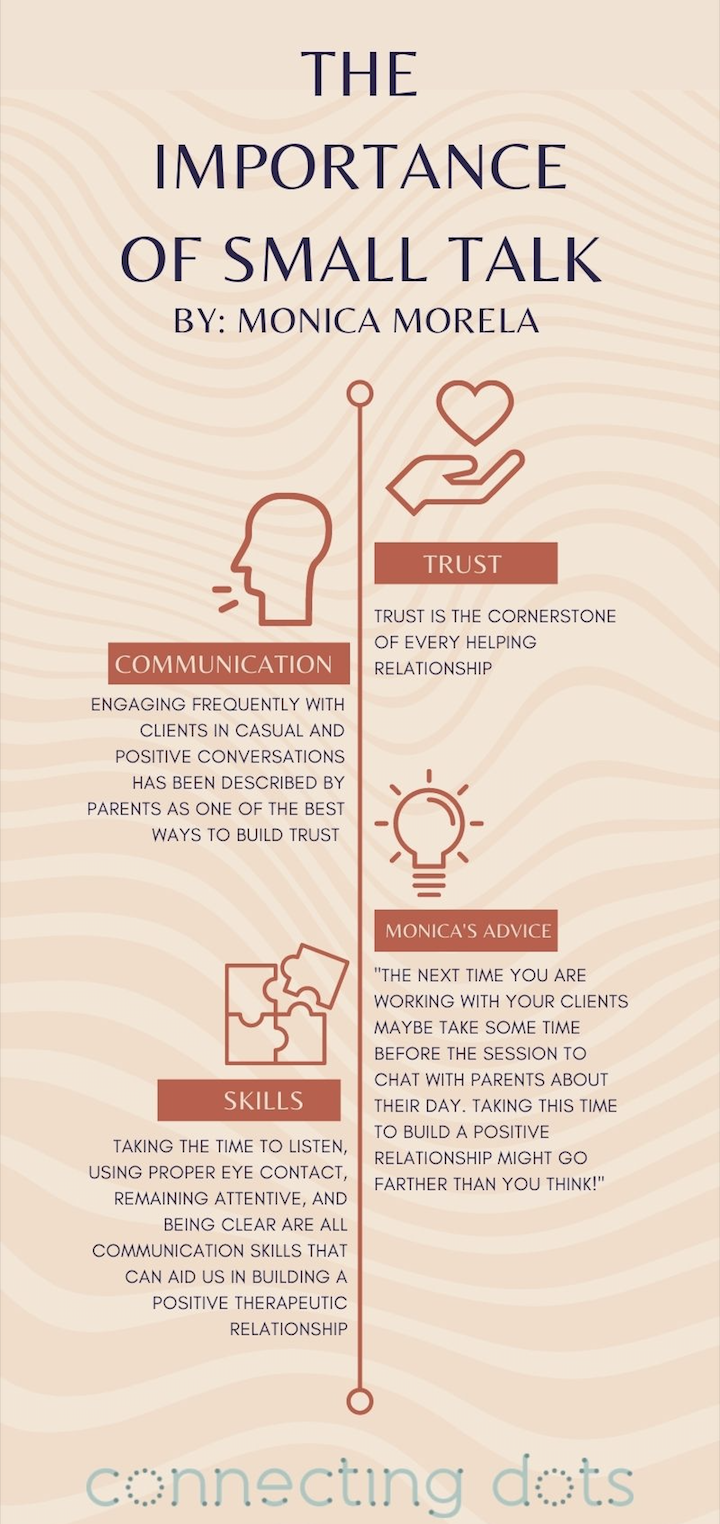

The Importance of Small Talk

By Monica Morela, behavioral aide with Connecting Dots

Lynne-McHale and Deatrick (2000) describe trust as being, “the cornerstone of helping relationships” (p. 211). This statement is also corroborated in Reeder and Morris’s (2018) qualitative study regarding the importance of trust in therapeutic relationships. They found that in some cases a positive therapeutic relationship was more strongly correlated with positive treatment outcomes than the choice of what treatments to use (Reeder & Morris, 2018). Reeder and Morris (2018) also found that although professionals are aware of the importance of trusting relationships, they were not always clear on how to achieve a positive trusting relationship with families. So how do we as practitioners and behavioural aides authentically gain the trust of the families we work with? The answer might be more attainable than we think! Francis et al. (2016) examined parent perceptions of best practices for building trust in professional relationships. They found that one of the most important skills for building trusting family-professional partnerships was communication (Francis et al., 2016). More specifically, engaging frequently with clients in casual and positive conversations has been described by parents as one of the best ways to build trust (Francis et al., 2016). This means that our beginning of session chats about the weather and our weekends might be more important than we think! Edwards et al. (2018) provide more detail regarding key communication skills that can help us as service providers build positive working relationships. Taking the time to listen, using proper eye contact, remaining attentive, and being clear are all communication skills that can aid us in building a positive therapeutic relationship.

Lynne-McHale and Deatrick (2000) describe trust as being, “the cornerstone of helping relationships” (p. 211). This statement is also corroborated in Reeder and Morris’s (2018) qualitative study regarding the importance of trust in therapeutic relationships. They found that in some cases a positive therapeutic relationship was more strongly correlated with positive treatment outcomes than the choice of what treatments to use (Reeder & Morris, 2018). Reeder and Morris (2018) also found that although professionals are aware of the importance of trusting relationships, they were not always clear on how to achieve a positive trusting relationship with families. So how do we as practitioners and behavioural aides authentically gain the trust of the families we work with? The answer might be more attainable than we think! Francis et al. (2016) examined parent perceptions of best practices for building trust in professional relationships. They found that one of the most important skills for building trusting family-professional partnerships was communication (Francis et al., 2016). More specifically, engaging frequently with clients in casual and positive conversations has been described by parents as one of the best ways to build trust (Francis et al., 2016). This means that our beginning of session chats about the weather and our weekends might be more important than we think! Edwards et al. (2018) provide more detail regarding key communication skills that can help us as service providers build positive working relationships. Taking the time to listen, using proper eye contact, remaining attentive, and being clear are all communication skills that can aid us in building a positive therapeutic relationship.

I think that we can treat building rapport and trust as a skill. Taking an intentional, conscious, and conscientious approach to providing care will be beneficial for us as practitioners but also for the families we work with. The next time you are working with your clients maybe take some time before the session to chat with parents about their day. Taking this time to build a positive relationship might go farther than you think!

References

Edwards, M., Parmenter, T., O’Brien, P., & Brown, R. (2018). FAMILY QUALITY OF LIFE AND THE BUILDING OF SOCIAL CONNECTIONS: PRACTICAL SUGGESTIONS FOR PRACTICE AND POLICY. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 9(4), 88–106. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs94201818642

Francis, G. L., Blue-Banning, M., Haines, S. J., Turnbull, A. P., & Gross, J. M. (2016). Building “Our School”: Parental Perspectives for Building Trusting Family–Professional Partnerships. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 60(4), 329–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988x.2016.1164115

Lynn-McHale, D. J., & Deatrick, J. A. (2000). Trust Between Family and Health Care Provider. Journal of Family Nursing, 6(3), 210–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/107484070000600302

Reeder, J., & Morris, J. (2018). The importance of the therapeutic relationship when providing information to parents of children with long-term disabilities: The views and experiences of UK paediatric therapists. Journal of Child Health Care, 22(3), 371–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493518759239

The Effects of Exercise on Major Depressive Disorder

By: Maryam Abro

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) generally known as clinical depression is very common and seriously challenging for the health care system due to its recurrent and treatment-resistant characteristics (Morres et al., 2019) and one of the leading causes of years lived with disability (YLD) (James et al., 2018 as cited in Pitsillou et al., 2020). MDD is a common disease and affects people of different ages and social backgrounds (Moussavi et al., 2007). It is estimated that depression affects 322 million people worldwide and the number of people living with depression increased by 18.4% between the years 2005 and 2015 (WHO, 2017).

MDD is no longer considered as a discrete disease with simple cause and symptom and believed to be “multidimensional” (Clark et al., 2017 as cited in Pitsillou et al., 2020). MDD is characterized by an assortment of “physiological”, “psychological” and “cognitive symptoms” and it is diagnosed based on a collection of specific symptoms as there are no objective diagnostic tests (Cullen, Klimes-Dougan, Kumara, & Schulz, 2009). The clinical description of depression is mood disturbance for example sad, low, or irritable mood or a persistent loss of interest or pleasure, and must be manifested with additional biological, cognitive, and emotional symptoms such as sleep disturbance, poor concentration, and feeling of worthlessness (Curry, & Hersh, 2014). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), MDD is categorized by peculiar changes in “affective”, “cognitive” and “neurovegetative” domain with symptoms lasting for at least 2 weeks. Moreover, five or more symptoms need to exist in the same event and at the minimum one of the signs as depressed mood or “anhedonia” and other symptoms being unexplained substantial weight change, fatigue or weakness, feelings of guilt or insignificance, difficulty concentrating and frequent suicidal thoughts (AMA, 2013 as cited in Pitsillou et al., 2020). Individuals with MDD become socially isolated and report decreased enjoyment in social connections (Bora & Berk, 2016) and are at greater risk of suicide. Suicide is the third leading cause of death in 10 to 24 years old and 50% of the time the cause is related to MDD (Cullen et al., 2009).

MDD is more common in adolescents than in younger children (Curry, & Hersh, 2014) and the prevalence in women is double as compared to men. MDD follows a recurrent course and on average individuals experience five to nine Major Depressive Episodes (MDEs) and with each recurrence, the time between episodes becomes shorter and shorter (Pizzagali, Whitton, & Webb, 2018). Depression damages health to a greater extent than any other disease (Moussavi et al., 2007) and is “highly comorbid with other mental disorders, most prominently anxiety disorders (59%), impulse control disorders (32%), and substance use disorders (24%), and collectively almost 75% of adults with lifetime MDD report at least one other lifetime DSM disorder” (NCS Replication; Kessler et al., 2011 as cited in Pizzagali et al., 2018). Several studies have suggested that MDD is connected with neurocognitive damage mainly in attention and “executive function” and severity of depressive symptoms are directly related with cognitive difficulties (Bora et al.,2013; Lee et al.,2012; Snyder, 2013; Trivedi and Greer, 2014; Wagner et al.,2012; McDermott and Ebmeier, 2009 as cited in Bora & Berk, 2016). Furthermore, MDD is also linked with other illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, arthritis, asthma, and chronic pain (Baxter, Charlson, Somerville, & Whiteford, 2011 as cited in Pizzagali et al., 2018). Due to comorbidity with other mental and physical illnesses, the individuals suffering from MDD have a greater risk of premature mortality and generally have approximately 10–15 years shorter life expectancy (Gerber, Holsboer-Trachsler, Pühse, & Brand, 2016).

The traditional treatment for MDD is pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy or a combination of both (Gerber et al., 2016). In severe cases of depression, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) can also be used (Pandarakalam, 2018 as cited in Pitsillou et al., 2020). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are some of the standard medication used for treatment of MDD (Gelenberg et al., 2010). These drugs act on the monoamine system and increase the availability of serotonin (5-HT), norepinephrine and dopamine in the brain (Pitsillou et al., 2020).

The “heterogeneity” of depression poses serious challenges for traditional treatments (Kandola, Ashdown-Franks, Hendrikse, Sabiston, & Stubbs, 2019). The treatment outcome for pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy are not broad and 34% of people with depression tend to be non-responsive to treatment (Cipriani et al., 2018; Cuijpers et al., 2019; Rush et al., 2006 as cited in Kandola et al., 2019). Currently, antidepressants are prescribed on a ‘trial and error’ approach (Serretti, 2018 as cited in Pitsillou et al., 2020) and it is estimated that only 30% to 50% of patients respond to “single-action” or “dual-action” monotherapy and majority of patients require change or increase in medication (Gerber et al., 2016). Furthermore, antidepressants can cause various side effects (Anderson et al., 2012 as cited in Kandola et al., 2019).

The traditional treatments for depression such as pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy will continue a pivotal role in the treatment, however, considerable number of people with depression do not pursue treatment and more than 50% of patients, who even seek treatment do not respond effectively and require additional treatment options, which most of time do not provide remission. Consequently, new and complementary treatment options are urgently need (Gerber et al., 2016; Kandola et al., 2019). Physical activity has proved to be effective alternative option for the treatment of depression (Karg, Dorscht, Kornhuber, & Luttenberger, 2020).

Effects of Exercise

Notwithstanding widespread research on the effectiveness of exercise, the exact mechanisms through which antidepressant effects are produced have not been established. It is believed that exercise produces antidepressant effects through numerous biological and psychosocial avenues (Kandola et al., 2019).

Biological Mechanisms

The neurobiological mechanism theory suggests that physical activity increases cognition and mental health by changes in the structural and functional composition of the brain (Lin, & Kuo, 2013; Dishman, & O’Connor, 2009 as cited in Lubans et al., 2016). Voss et al (2013) described three main categories that are impacted by exercise:

- Cells, molecules and circuits;

- Biomarkers- gray matter volume, cerebral blood volume, flow;

- Peripheral biomarkers- circulating growth factors, inflammatory markers (as cited in Lubans et al., 2016).

Several meta-analyses have discovered the relation between depression and structural abnormalities in the brain such as a decrease in hippocampal, prefrontal, orbitofrontal, and anterior cingulate cortex volumes (Bora et al., 2012; Du et al., 2012; Kempton et al., 2011; Koolschijn et al., 2009; Lai, 2013; Sacher et al., 2012; Schmaal et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2014 as cited in Kandola et al., 2019). In people with depression, the hippocampus is the commonly affected area in the brain (Schmaal et al., 2015 as cited in Kandola et al., 2019). The hippocampus is associated with emotional processing and stress regulation and these regions are mainly affected by depression (Zheng et al., 2019; Dranovsky and Hen, 2006 as cited in Kandola et al., 2019). Animal models suggest that depression impairs various cellular processes, including hippocampal neurogenesis (Anacker et al., 2013; Eisch and Petrik, 2012; Hill et al., 2015; Sahay and Hen, 2007 as cited in Kandola et al., 2019) and it is believed that decreased rates of hippocampal neurogenesis are partly accountable for depressed mood (Duman, Heninger, & Nestler, 1997 as cited in Rethorst et al., 2009).

It is believed that antidepressant effects of exercise are related to physiological changes that triggers hippocampal neurogenesis (Ernst et al., 2006 as cited in Rethorst et al., 2009). In animal studies, it has been observed that exercise results in changes in brain-derived neurotropic factor (BDNF), increase in cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation. Further, it stimulates the growth of new capillaries that are vital for the transportation of essential nutrients to neurons and results in an increase in neurochemicals, e.g. brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) ( Van Praag, 2008; Kleim, & Cooper, 2002; Cotman, Berchtold, & Christie, 2007 as cited in Lubans et al., 2016).

Inflammation

Several meta-analyses, Dowlati et al. (2010); Howren et al. (2009); Köhler et al. (2017); Valkanova et al. (2013), suggested that people with depression have raised levels of pro-inflammatory markers, including Interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1, Tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), C-reactive proteins (CRP) and several other IL receptors and receptor antagonists (as cited in Kandola et al., 2019). Inflammation can interrupt several pathways involved in depression e.g., “dysregulating BDNF” or “neurotransmitter systems” via “kynurenine pathways” (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2015; Calabrese et al., 2014; Cervenka et al., 2017; Schwarcz et al., 2012 as cited in Kandola et al., 2019).

Studies have noted reduction in number of “circulating inflammatory factors” such as IL-6, IL-18, CRP, leptin, fibrinogen and angiotensin II due to exercise (Fedewa et al., 2017, 2018; Lin et al., 2015 as cited in Kandola et al., 2019). In a recent Randomized control trials (RCT) on 98 participants with MDD by Euteneuer et al. (2017), an increase in anti-inflammatory marker IL-10 in the plasma was observed in experimental group- undergoing CBT with exercise as add on (as cited in Kandola et al., 2019). Similarly, in another 12-week study, reduction in depression symptoms and serum samples of pro-inflammatory IL-6 was noticed due to exercise (Lavebratt et al., 2017 as cited in Kandola et al., 2019).

Psychosocial and Behavioral Mechanism

People with depression have lower levels of self-esteem that could be potential reason for sense of worthlessness (Keane and Loades, 2017; Orth et al., 2008; Van de Vliet et al., 2002 as cited in Kandola et al., 2019). A negative association exists between weight status and mental health. People who have dissatisfaction with body image have higher risk of depression and show significantly lower scores on physical self-perceptions (Ali et al., 2010; Tang et al., 2010; Jackson et al., 2014; Van deVliet et al., 2002 as cited in Kandola et al., 2019).

Cross-sectional studies suggest that physical activity is linked with higher self-esteem scores, QOL and positive affect due to physical self-perception (Feuerhahn et al., 2014; Sani et al., 2016 as cited in Kandola et al., 2019). Legrand (2014) found that 7-week exercise intervention resulted in increases in physical self-perception, self-esteem, and decreases in depressive symptoms in women with elevated depressive symptoms (as cited in Kandola et al., 2019). Further, physical activity assist contact with the natural environment and could improve mood that affect wider affective states and other signs of well-being (Deci, & Ryan, 2002; Ryff, & Keyes, 1995 as cited in Lubans et al., 2016). Ossip-Klein et al (1989), in a study of clinically depressed women, found that exercise, both aerobic and resistance training, resulted in increased self-esteem and a decrease in depressive symptoms. The authors suggested that an increase in self-esteem may be responsible for decrease in depressive symptoms and contributed to higher self-esteem to improved body image and increased mastery (as cited in Rethorst et al., 2009).

The behavioral mechanism theory contends that changes in mental health outcomes due to physical activity are facilitated by changes in applicable and related behaviors, for example, involvement in exercise may result in better sleep length, sleep effectiveness, sleep latency and reduce sleepiness. Furthermore, partaking in physical activity may also affect self-regulation and coping skills that have potential implications for mental health (Stone, Stevens, & Faulkner, 2013; McNeil et al., 2015; Lang et al., 2013; Gaina et al., 2007 as cited in Lubans et al., 2016). Meta-analytical studies have displayed that exercise increases total sleep, increases slow-wave sleep, and decreases REM sleep resulting in a substantial decrease in Serotonin discharge during REM sleep (Kubitz et al., 1996; Youngstedt, O’ Connor, & Dishman, 1997; McGinty, & Harper, 1976 as cited in Rethorst et al., 2009).

Safety in the Community

Vulnerable Person Self-Registry (Calgary Police Service)

Vulnerable Person Self-Registry (Calgary Police Service)

https://www.calgary.ca/cps/community-programs-and-resources/diversity-resources/vulnerable-person-self-registry.html

This is now done through MedicAlert, which is a registered charity that offers flexible subscription plans and financial assistance to those who need it. There is a small fee to subscribe.

Through the MedicAlert Connect Protect program, Emergency Communications Officers at Calgary 9-1-1 will have 24-hour direct access to every MedicAlert subscriber’s recent photo and personal information including identity, physical descriptions, condition descriptions, medical needs, wandering history, and behavior management strategies such as anxiety triggers and de-escalation techniques. The database also includes emergency contact information, allowing first responders to quickly contact a subscriber’s loved ones. IDs can take any form that works for the subscriber, including watches, jewelry, or even shoe tags. See https://medicalert.ca/

Preparation

Dress children in bright-colored clothing so they can easily be spotted. Lemon yellow and lime green are the suggested colors because they easily attract the eye. You might also have a piece of clothing that is only worn when the child goes out in public so you can easily remember what they are wearing

Take a photo of your child with your phone before you leave home or when you arrive at your destination. This will help police find a lost child because they will be aware of exactly what the child is wearing, and how they look that day.

Discuss a designated place to go if you get lost or advise children to stay right where they are when they feel they are lost. Tell children to find a security officer, police officer or an employee if you are in a public place or remind them that they can ask another adult with kids for help.

Prepare your child so that they can identify themselves. For younger children, have their identification information in their pocket. If they able to speak and can relay the information, practice reciting your phone number with them, and let them know they can always call 911.

Positive reinforcement is the best way to prevent a child from wandering away from you when you are in a public place. Praise your child for staying close to you. Speak with your child about stranger danger and remind them of the importance of staying with you. Social stories can be effective ways to describe a situation and the appropriate social or behavioral responses for that situation.

What to do if your child is lost

If you are at home, search your house first before going outside. Check closets, laundry baskets and piles of clothes, in and under beds, in large appliances, in vehicles and other areas where the child may hide or play.

If you still can’t find the child in the home, call 911 to notify them and let them know if you feel the child is in any danger. Police departments would rather be aware of the situation and called back when the child is found, rather than wasting valuable minutes to find the child. Time is crucial once a child has been separated from you.

In the community- many public places have standard procedures of what to do when a child is missing, so call 911 to make sure authorities and the venue’s management are notified that the child is lost. Authorities will be able to help because they are familiar with the area’s surroundings and could have the capability to lockdown buildings or issue an alert.

GPS Apps

AngelSense- https://www.angelsense.com/

Trax Play- https://traxfamily.com/

Weenect- https://www.weenect.com/en/kids-gps-tracker/

Giobit- https://www.jiobit.com/

My Buddy Tag- https://mybuddytag.com/

(not an exhaustive list)

Resources:

Calgary’s Child- https://www.calgaryschild.com/health-and-safety/safety/954-im-lost-how-to-prevent-and-handle-a-lost-child-situation

https://www.autismparentingmagazine.com/best-gps-tracker-for-autism/

https://www.angelsense.com/

https://www.safewise.com/resources/wearable-gps-tracking-devices-for-kids-guide/

https://www.calgary.ca/cps/community-programs-and-resources/diversity-resources/vulnerable-person-self-registry.html

Coping Through Covid

How are you doing? Really, how are YOU doing? In asking other people how they are doing, I have generally heard the answer, “good,” and then a pause, followed by a “well….” and we jump into a list of things that including “excesses” and “deficits,” otherwise known as “mores” and “less thans.” More tantrums, crying, frustration, screen time, online burnout…more overall stress. And then the deficits. Lower motivation, less time and space to exercise, outdoor time (so cold lately), missing connection with friends and family, less energy to meet life’s demands.

How are you doing? Really, how are YOU doing? In asking other people how they are doing, I have generally heard the answer, “good,” and then a pause, followed by a “well….” and we jump into a list of things that including “excesses” and “deficits,” otherwise known as “mores” and “less thans.” More tantrums, crying, frustration, screen time, online burnout…more overall stress. And then the deficits. Lower motivation, less time and space to exercise, outdoor time (so cold lately), missing connection with friends and family, less energy to meet life’s demands.

Most people I have talked to are having a tough time. But how do you know if you are coping or not? What is coping? What does it look like for you?

So, the first question, are you coping or not and how do you know? I’ve heard a good phrase recently; A problem is not a problem until it becomes a problem. Can you get out of bed? Can you make it to the shower? Are you getting to work? Can you meet your daily life’s demands? The American Psychological Association defines coping as the use of strategies (thinking/cognitive or behavioral) to manage the demands of the situation, when such demands exceed our own personal resources; or how we reduce the impact of stress. So, what we do to make things more manageable when we feel, well, “zoomed out.”

How do you cope? I can tell you how I cope. The most important thing for me (and the hardest, of course) is setting boundaries, saying ‘no,’ and not doing too much.’ As much as I’d like to connect with everyone on Zoom, I often get ‘zoomed-out.’ As hard as it is to say no to these (sometimes) it is nice to just sit and be. But then I know the importance of connection and how that can fuel me and my overall motivation to get things done in life. Again, balance is hard, but I’m trying (as I know you are too!). There are other ways to cope. This can include a conscious approach to problem-solving, a thought process when meeting a stressful situation, or how you try to modify your reaction to a situation.

I wish I could tell you the best way to cope, or how to cope with Covid, but please know you’re not alone out there. Think about it, how do you cope? Are you coping? And if not, please reach out to your Connecting Dots team. We’re here to help you figure out the best way for you and your family to cope through Covid. And I say “through” because we ARE going to get to the other side of this. xo

For more information on coping: https://dictionary.apa.org/coping

Effects of Stress On The Brain

Effects of Stress On The Brain: How stress can affect the human brain in different stressful situations

By: Maryam Abro

To understand the common feeling of “stress” on the human brain, we need to understand the definition.

Carter (2007) defines stress as:

“A person-environment, biopsychosocial interaction, wherein environmental events (known as “stressors”) are appraised first as either positive or unwanted and negative. If the appraisal is that the stressor is unwanted and negative, some action to cope and adapt is needed. If coping and adaptation fail, one is to experience stress reactions.”

Stress is a result of uncertain, adverse, random, and overwhelming events. Stress is greater if there are already problems and struggles in one’s life. Stress reactions arise regardless if stressors are “objective” or “subjective” and long-term exposure can result in negative psychological consequences, ranging from mild to severe.

It is believed by Carlson, (1997), that people who are experiencing severe stress react in one or more of the three fundamental reactions that are presented by one or more “physiological, emotional, cognitive, or behavioral modalities. The core reactions are:

- Intrusion or reexperiencing

- Arousal or hyperactivity

- Avoidance, or maybe even physical numbing”

Unfortunately, stress is a word used frequently in modern-day society, often used to describe the experiences that cause anxiety and frustration because they make individuals feel insecure and leave them with the feeling that they wouldn’t be able to successfully cope with situations that they may be facing.

Nowadays, there are many different stressors, especially during the Covid-19 global pandemic. Some of the stressors that may occur due to Covid are new rules causing changes and making new normal for individuals, social distancing, problems at an individual’s job or home, financial worries, etc. It is certain that these stressors would be, or have been deeply amplified due to our current circumstances with Covid-19 as well. Sometimes, these stressors can have serious implications, for example, effects of social distancing and isolation on mental health, loss of livelihood because of shutting down businesses, deaths caused by drugs and alcohol during the pandemic, increase in domestic violence, etc. Also, they may trigger the human “flight or fight response”. Besides creating daily annoyances in life, these stressors can lead to chronic stress, or maybe even PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), which is an aftereffect of a tragic experience.

The life experiences described above are the most common stressors that trigger human beings and cause their behavior to change in a certain way. For instance, being “stressed out” may create anxiety and depression, insomnia, and excessive substance abuse like drinking, or smoking. Some individuals may even resort to using medications such as “anxiolytics”, benzodiazepines, and sleeping pills to get rid of stressful thoughts. The prolonged use of such self-medication can result in various negative health outcomes.

The human brain itself is responsible to select the experiences that cause stress and it also categorizes the behavioral and physiological reactions to the stressful events, which can promote or deteriorate health. Acute and Chronic Stress has been shown to cause changes in the brain and affect many systems in the body like “neuroendocrine, autonomic, metabolic, cardiovascular, and immune”.

As discussed earlier, it is well believed that stress causes changes in the brain. Now, the question at hand is: what Kind of change does stress cause in the human brain? To find out what kind of changes take place in the human brain, we need to explore the effects of stress in different parts of the brain.

Extreme Acute and chronic stress may cause effects on the amygdala’s stress response through three core regulatory systems: “the serotonergic system”, “the catecholaminergic system” and the “HPA axis”.

The advancement of brain imaging techniques has enabled researchers to examine the neural circuit activity changed by acute stress in humans. MRI studies have revealed that the subjects who listened to stressful events related to their life had increased response of blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) in the medial PFC (anterior cingulate cortex), particularly in the right hemisphere indicating the anterior cingulate cortex’s part in processing mental suffering. Studies conducted on humans also reported how drastic stress affects the dlPFC operations, participants who had been exposed to stressful videos, displayed poor performance of N-back working memory, and reduced BOLD activity over dlPFC. Results also revealed that severe stress ended the normal deactivation of the default mode network. The subjects who had greater levels of catecholamine had more stress causing damage to working memory performance and reduction in dlPFC activity. There is a correlation between stress-induced catecholamine release and poor working memory performance. Exposure to unmanageable stress and higher catecholamine levels together impair the higher cognitive functions of PFC.

The hippocampus performs some of the higher tasks in the brain, such as encoding, storing, and retrieving information. Once it receives the messages from the axons, this information is processed through different synaptic mechanisms. The hippocampus sorts out the information and differentiates between important and less important information. Exposure to acute stress makes the hippocampus open to attack. Minor and short-duration stress normally increases hippocampal operation by increasing “synaptic plasticity”.

Stress impacts learning and memory tasks in humans and animals by changing the structure of hippocampal neurons . These alterations occur in different stages, starting from the changes in the synaptic memory to the changes in the dendritic branches . Most drastic effects of long-lasting stress on the hippocampus is a decrease in the pyramidal cell dendrites branches. The amount and form of “synapse-bearing spines” are active and are controlled by “factors including neurotransmitters, growth factors and hormones that, in turn, are governed by environmental signals, including stress”.

The information discussed above highlights some of the crucial structures of the brain and their response to stressful events. Many other areas need to be examined in this connection, such as loss of synaptic connections, dendrites, spine and “the generality of the stress response to other high-ordering association cortices, and how genetic insults interact with stress signaling pathways to hasten disease”. Stress and its effects on the brain is a vast area of research. The crucial point for future research is to unravel how different mechanisms few of those mentioned above (CRH, neuropeptides, neurotransmitters) respond to stress hormones such as adrenal and stress-associated neurotransmitters. It could be a challenging task to study the joint role played by these mechanisms to alter the hippocampus in response to stress. Further research would be required to uncover some of the effective treatments and helpful approaches to handle the drastic effects of both acute and short-term stress.

Connecting with Kindergarten: Who Teaches What?

By: Elizabeth Wotherspoon

Kindergarten can be a controversial and/or stress inducing topic for many. In Alberta, parents have the choice to either put their child in kindergarten or wait to start school until grade one. So, should you put your child in kindergarten or should you let your child be a kid for another year and wait for grade one? Waiting wouldn’t be an option if it was going to be a setback for your child in any way, right?

Let’s talk about exactly what your child can get from being part of a kindergarten class. The Kindergarten Program Statement (Alberta Education, 2008) provides learner expectations in seven learning areas. The expectations of these learning areas are not only accomplished in the Kindergarten program, but from the homes and communities of children as well. However, Kindergarten does provide some opportunities for children that simply cannot be taught at home. This is because a lot of what a child learns in kindergarten is taught by his or her peers. The following, separated by the seven learning areas, is a brief overview of what your child can get out of a Kindergarten class that he or she may not get anywhere else.

Early Literacy

This focuses on children being actively engaged in learning language and forming their own understanding of how spoken and written language works. A kindergarten program provides opportunities to:

- Experiment with language and to test it in verbal interactions with their peers and adults (other than their parents)

- Participate in shared listening, reading, and viewing experiences

- Sharing stories using rhyme, rhythms, symbols, pictures, and drama

- Class and group language activities

- Begin using language prediction skills

- Ask questions and make comments

- Represent and share ideas and information about topics of interest

Early Numeracy

Provides activities that foster a curiosity about mathematics. A kindergarten program provides the following opportunities that create interest in numeracy:

- Comparing quantities, searching for patterns, sorting objects, ordering objects, creating designs, and building with blocks

- Connects numbers to real-life experiences

- Develops mathematical reasoning skills (a foundation for later success)

- Develops problem-solving skills

- Being involved in a variety of experiences and interactions within the environment helps develop spatial sense including, visualization, mental imagery, and spatial reasoning

Citizenship and Identity

This focuses on the development of a strong sense of identity, self-esteem, and belonging. Children are given the opportunity to explore who they are in relation to others – a difficult thing to teach from home. All the children from a Kindergarten class bring their own perspectives, cultures, and experiences to the classroom. Because everyone has a unique background, bringing all the children together provides opportunities to:

- Become aware of who they are as unique individuals

- Express themselves by sharing personal stories

- Discover how they are connected to other people and their communities

- Express interest, sensitivity, and responsibility in their interactions with others

Environment and Community Awareness

By providing opportunities for children to use their five senses to explore, investigate, and describe their environment and community children become more aware of their surroundings. Using simple tools in a safe and appropriate manner provide experiences that allow children to:

- Recognize similarities and differences in living things, objects, and materials

- Learn about cause and effect relationships

- Make personal sense of the environment

- Explore familiar places and things in the environment and community

- Recognize seasonal changes in their environment and community

- Recognize familiar animals in their surroundings

Personal and Social Responsibility

In order for children to be able to learn, they need to be able to regulate their bodies. An unregulated child will spend all of his or her energy focusing on what is happening in his or her body and cannot attend to what is being taught. This area focuses on the personal and social management skills necessary for effective learning. Each child develops these skills at their own rate and is dependent on personal experiences; however, kindergarten provides children opportunities to:

- See themselves as capable learners by participating in learning tasks, trying new things, and taking risks

- Follow rules and learn the routines in a school environment

- Become more independent

- Develop friendship skills

- Demonstrate caring and contributing to others

- Express their feelings in socially acceptable ways

- Take turns, contribute to partner and group activities, work cooperatively, and give and receive help

Physical Skill and Well-Being

By participating in physical activities, by becoming aware of healthy food choices, and by learning safety rules, children develop positive attitudes towards an active, healthy lifestyle. Kindergarten provides practice opportunities for the behaviours that promote wellness. Children in kindergarten begin to develop a personal responsibility for health, learn about personal safety, and ways to prevent/reduce risks. Through play, the following skills are targeted:

- Coordinated movement, balance, and stability

- Finger and hand precision

- Hand-eye coordination

Creative Expression

Kindergarten gives children an environment where they can practice fostering respect and collaboration with others through sharing ideas and listening to others’ diverse views and opinions. Being involved in listening to others’ perspectives allows children to learn that people see and learn things in different ways than they do. The following are activities that help to develop these skills:

- Viewing and responding to natural forms, everyday objects, and artwork

- Individual and group musical activities, songs, and games

- Listen to (and begin to appreciate) a variety of musical instruments and different kinds of music

- Dramatic play and movement

- Helps with growth in self-awareness and self-confidence

Kindergarten helps to form the base knowledge so your child is ready for English language arts, math, social studies, science, physical education, health, and fine arts throughout elementary school. Children learn these skills at home, in the community, and in the kindergarten classroom. It is unlikely your child would be far behind without the experience of Kindergarten; however, certain skills such as knowing the routine and expectations of a school environment may be something a child who did not attend Kindergarten will have to learn.

Connecting with Kindergarten: Are They Ready?

By Elizabeth Wotherspoon

In my experience, a big stressor for parents is the concern that their child is not “ready for kindergarten.” This looks differently for everyone, some parents may be worried that their child mumbles through the L-M-N-O-P cluster in the alphabet song and others might be concerned with counting, colours, and writing skills. So, what exactly is your child required to know before entering Kindergarten?

After an extensive search for Kindergarten readiness checklists and articles that state what a child needs to know before entering Kindergarten, I came up short. The only identified requirements for a child to have met before entering Kindergarten is that they must be at least 4 years old on or before March 1st to start Kindergarten in September of the same calendar year.

With that in mind, starting Kindergarten is a big step and there are some things you can do to help your child adjust to starting school!

- Encourage your child to get dressed alone, including putting on shoes (remember, the laces might still be tricky).

- Take your child to the school playground.

- Encourage your child to follow 3-step directions. Example: “Find your crayons, make a picture, and bring it to me.”

- When your child comes home from school, avoid open-ended questions and ask specific ones instead. Example: “Tell me about the story your teacher read today.”

- Establish a consistent bedtime for your child.

Kindergarten has a curriculum, and even though there are no prerequisites for Kindergarten, here are some things you can do at home while your child is learning at school.

Children learn some basic colours and shapes in Kindegarten. You can help your child become more aware of colours and shapes in the following ways:

- Give your child options that require him or her to label colours. Example: “Do you want to wear the blue sweater or the red sweater?”

- Be a shape and colour detective while you’re walking around the neighbourhood. See who can find the most shapes and colours.

- Make Play-Doh at home, experimenting with food colouring and creating different shapes.

- Get your child to help with sorting laundry by matching socks by size and colour.

Kindergarten introduces the letters of the alphabet and the sounds those letters make. You can increase your child’s awareness of letters and sounds in the following ways:

- Trace letters with your finger on each other’s backs and guess what letter has been traced.

- Have your child think as many rhyming words as possible for simple words like “cat” or “bee.”

- As your child prints their name on crafts and cards, say the correct letter name.

In Kindergarten, some base skills for math are introduced such as, counting groups of objects from 1-10, learning about patterns, and learning about measurements. You can help your child become more aware and interested in math at home by:

- Counting the plates with your child as you set the table.

- Baking together using words such as “empty”, “full”, “more”, or “less” as you add ingredients.

- Playing games like “Snakes and Ladders”, “Memory”, and “Go Fish.”

- Encouraging your child to look for patterns in his or her clothes and around the house.

Kindergarten is an important time for your child to develop friendship skills. They are learning to show a positive and caring attitude toward others. You can help your child develop and practice his or her social skills by:

- Allowing/encouraging your child to have a play date and share toys.

- Encouraging your child to help friends or family members by doing things like holding a door open.

- Getting your child to help with making supper by giving him or her simple jobs. While doing this, talk about the names of the foods and utensils being used.

- Encouraging your child to create cards or gifts (something special) for friends and family members

Children start to learn about science by investigating living things in Kindergarten. You can help your child learn more about living things by:

- Having your child name each animal while looking at pictures in books or on a trip to the zoo. Talk about where the animals live, what they might eat, and the noises they make.

- Read simple stories to your child. After reading the story, ask what happened at the beginning, middle, and end, of the story.

- Making animal puppets out of paper bags or socks and have a puppet show.

In Kindergarten, children learn about time. They talk about the days of the week, months of the year, and the seasons. You can help your child become more aware of time in general and the seasons by:

- Using a calendar at home to talk about the day, date, and month of the year.

- Go for a walk and look for signs of autumn, winter, and spring.

- Go on a treasure hunt for different sizes and colours of leaves and pinecones and then make a craft out of them.

- Have your child help you rake the leaves in your yard. Have fun jumping in the leaves, throwing, and catching them.

- Have your child help you shovel the sidewalk.

- Playing in the fresh snow. Making different footprints, snow angels, and snowmen and going tobogganing.

- Making paper snowflakes.

- Encourage your child to talk about the changes they can find outside (e.g., the snow is melting, the leaves are growing, the grass is getting green) in spring.

- Encourage your child to hang up this or her jacket and hang their jacket when they come home from school to develop a sense of responsibility at home.

Now that you know there are no requirements (other than age) to be ready for Kindergarten, you can send your little one of to his or her first day of school with confidence. Have fun and enjoy this exciting time in your child’s life!