Overcoming fear by providing a therapeutic environment

By: Asmaa Fellah

Starting school (including preschool and kindergarten) is a major transitional event in children’s lives. With transition comes change, and with change comes coping and adapting. For many children, coping with change can be very daunting and intimidating, especially when children have fears. Children are scared of being away from their parents in a new setting and environment. In addition, they are also scared of rejection, meeting new people, and failure.

In kindergarten, many children begin to feel separation anxiety and will start crying, yelling, screaming, and throwing temper tantrums, especially on the few first days. Children are attached to their parents, and therefore feel a sense of securement when their guardians are in their environment. Rather, when children are away from their guardians for the first time and for long periods of time, he or she feels lonely and scared. Not only do they feel scared, but their environment also is completely new to them and they feel lost and overwhelmed. Their sense of securement is instantly gone, leaving them with a sense of fear from their new environment. This is a commonly seen fear amongst kindergarteners.

As children continue in their schooling, expectations and accomplishments are expected from teachers and parents. Homework and assignments are expected to be completed, inside school grounds and outside school grounds. Fear of failure starts to arise as children may be overwhelmed with how much they need to get done, or maybe the difficulty of the tasks, or the pressure of parents and teachers. Fear of failure may prevent them from enjoying school as it will feel forced and unwanted. In addition, children may think that if they don’t meet these expectations and complete their work, a harsh consequence may be set.

The mentioned fears and concepts are applicable to how protentional feelings a child might feel prior to and during an in-home service. Remember, you are a complete stranger to this child and in their point of view, you might be invading their territory. In addition, that child doesn’t have other children around him or her, so they might feel more singled out leading to increased feelings of fear. Now how do we overcome this?

Time and patience. One must understand the difficulty that a child endures when trying to become comfortable and opening up to strangers. In a situation where an in-home aide only has 4 hours, this becomes exceptionally more difficult as it takes longer for the child to become comfortable and adapt.

Second, it is crucial to provide a therapeutic environment that includes the least restrictive environment is necessary for children’s growth and development. A least restrictive environment (LRE) is incorporated in a therapeutic environment. The more negative and unsafe environment, the more children are least likely to learn appropriate behavior to adapt to new environments and events. Proper educational and behavioral support includes an LRE that incorporates a therapeutic and engaging environment, allowing students to prosper and flourish intellectually, emotionally, and socially.

When a student feels safe, he or she is more likely to engage in actions and adventure outside of their confront zone. On the other hand, a student is more likely to present inappropriate actions such as not listening, and engage in inappropriate behavior if the safety component is not presented in their environment. Students use these tactics as a defense mechanism in order to create a sense of safety. A safe environment also creates a sense of welcome and is composed of mutual respect, no-judgment rule. When teachers engage in welcoming actions such as smiling at their students and asking how they’re doing, the students are less likely to be guarded and rather open up and show their true selves. Providing a no-judgment rule allows for students to feel safe to take new opportunities, experiment with new strategies, and engage in new appropriate behavior.

An LRE environment speaks about the accessibility to preferred activities for exceptional students which in turn increases responsiveness to new behavior. Much the same as adults, youngsters have interest and preference which makes them more inclined to complete a task when these are available. Students are also more likely to rebel against the teacher which results in inappropriate behavior if the task is too boring or too demanding. It is important to relate academic and non-academic tasks to the preferences of the exceptional student when possible. When tasks personally relate to the student, he or she is more like to be engaged in the activity. The accessibility to preferred activities also fosters creativity and active learning for these students. Realistically, not all tasks are relatable to different interests nor appeal to students, rather rewarding them after a completed task with an interest of theirs is also effective. For example, a reward for a student who enjoys reading could be ten extra minutes of preferred reading after finishing a math worksheet. Using these techniques increases the chances of responsiveness and participation for all students and can in turn lead to increased active learning.

To summarize, utilizing these strategies allows aides to create a sense of security and welcoming. We all must be patient in regards to children opening up. It is crucial to allow enough time, create a positive atmosphere and allow the child to engage in activities they love. These strategies not only benefit’ the aides but also allows students to take risks and new attempts without feeling embarrassed or afraid.

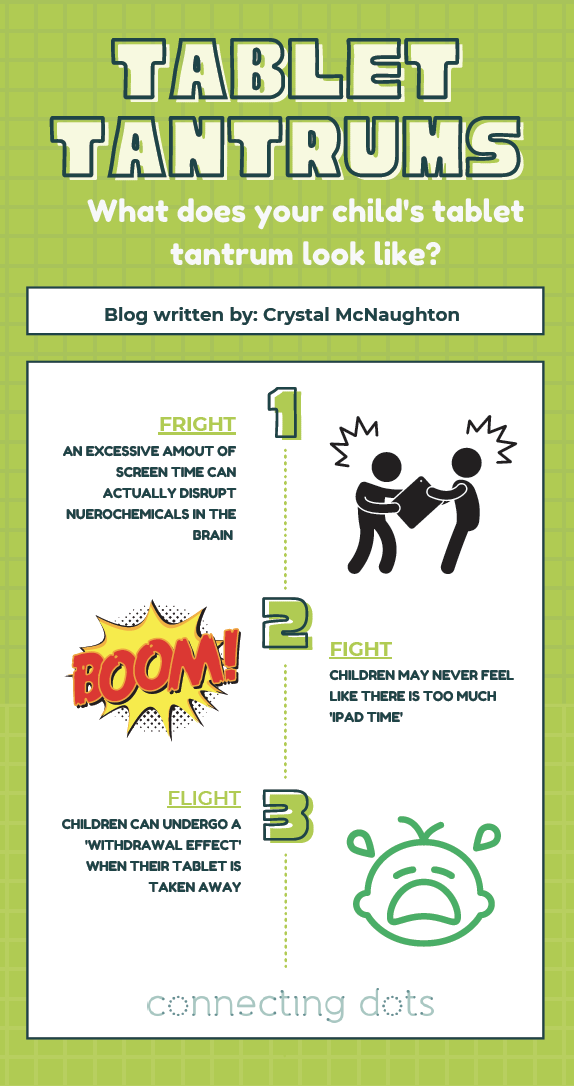

Tablet Tantrums

By: Crystal McNaughton

Does your child turn off the screen/IPad/tablet when you ask? How many times do you have to remind your child to turn it off? Maybe I’ll rephrase the question….how many times do you have to nag/yell at your child to turn off their tablet? (or does this just happen at my house?) Does your child kindly turn their screen off and easily move on to another activity? Oops, rephrase again…What does your child’s “tablet tantrum” look like?

If your child does easily turn off their screen and calmly refocus themselves on something else, can you please call me? Because I need to know your secret!

I have had many, many parents tell me about how hard it is to get their child to ‘transition from the tablet’ and explain how challenging their behaviors are after the tablet is gone. I’ve witnessed it myself when I tell (okay nag) my kids to turn off their tablets, sometimes ending up grabbing it from them. What usually happens is they scream, yell, or break down in tears. Next, they start fighting. The older one sits on the younger one. The younger one bites the older one. I’m left feeling exhausted and overwhelmed, as well as that good ol’ parent guilt for letting them watch their tablets too much. If this sounds familiar to you, please know, it’s not just you. It’s not just your child.

There’s a reason behind the ‘tablet tantrum.”

When kids are on a screen or tablet, it looks as if they are quiet, sitting, focused, and calm. Actually, what is happening in their brains at this time is the opposite. A number of neurochemicals are required to be in balance in our kid’s brains, and tablets and screen time can disrupt this balance. Video games or other gaming can create a release of dopamine, which feels good for kids, thus they always want MORE. There is never enough.

Next comes an adrenaline response, which is the ‘fright/flight/fight’ response. The brain releases adrenaline which prepares the body’s stress response. Psychological stress can also trigger an increase in cortisol; the stress hormone. Take away the ‘feel good’ dopamine and we see a ‘withdrawal’ effect.

So, we ask a child to turn off their tablet, and what we see is an angry person pumped full of ‘fight or flight’ energy. A tablet tantrum.

Now what?

There are recommendations for screen time. I know things in this world are so stressful as it is, and I’ve definitely given my kids more screen time than I’d like to admit. But I’m trying. We’re all trying.

If you want to check-in and see what is a recommended amount of screen time for your kid, take a look here: https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Children-And-Watching-TV-054.aspx

Taking away the tablet from your child will usually be hard. But setting limits is important, as there will never be enough screen time if it were up to our kids. Take a deep breath, and remind yourself, that you’re setting limits, you’re doing what’s best for your child by enforcing those limits and encouraging breaks from the screen. If you want to make some changes, your Connecting Dots therapists are there to help you along the way. Remember, we’re all here with you during those tablet tantrums.

http://www.childassessmentandtraining.com/the-ultimate-explanation-about-the-great-screen-debate/

https://www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/mental-wealth/201211/screens-and-the-stress-response

Teaching the 5-W-H Questions: Part 4

By Christine Marchant

If you have read my previous posts, you’ll notice that I have a system for teaching 5-W-H questions. Levels one through three deal with concrete who, what, where, when, why, and how questions, while level four is concerned with asking the child about what can happen in the future. It’s quite easy to teach the first two levels. When the child becomes more aware of their world, and isn’t easily entertained by the simple flash cards or photos, the teaching becomes more challenging. I find that they are now more interested in the games. I like to try plenty of new games to test the child’s interest and to see if the game will match the goal. We play the game at least three times with no target goals. This is how I build the interest and desire to play the game. The goal here is to create a strong desire to play the game. At this level, it’s the game and the interactions with the people that keep the child involved and wanting to cooperate. It doesn’t matter what the game is, as long as you explain to the child that the reason you are doing the sessions is to help the child achieve the targets. Hopefully, at this level, you’ve already created a relationship of trust and honesty. This is my favorite level of the relationship with the child because they are opened enough to actually understand why you are spending the time with them. They are usually enthusiastic about achieving their goals. I explain to the child that we play the game with no targets and then when we really enjoy the game we add the targets.

While playing the games, I use a LOT of WE, US, OUR, and TEAM WORK language to motivate the child and let her know that we are working together. The language you use will determine the attitude of the child. They LOVE to take ownership of their learning. By this level, they seldom resist doing their “work.” The games are now a fun way to make the sessions go faster. They may MOAN and GROAN or ROLL their eyes, and declare “you’re the meanest aide EVER!!” BUT, it’s all said in laughter and good cheer. If you have a good relationship with them, you play along, then say, “OK! Let’s get down to business, and get it done. ” If you don’t have a relationship with the child and are just jumping in, don’t start at this level!! If I were to start teaching the 5-W-H without knowing the child, I would ALWAYS start at a lower level and see where the child is, then move up the levels, in the same order, at the speed that matches the child. This level is based entirely on trust and a relationship with the child.

Teaching what happens after is the trickiest part for children because it requires abstract thinking. It’s been proven that we can envision the past easier than the future. The future is difficult because it can be any possibility. The past now seems more concrete than the future because it’s easier to prove. If you have one of those children that LOVE to argue and declare that a dragon has super powers and can possibly run for government in the future, LET IT GO!!!! Don’t argue with the child, but try to remember the goal! At this point, the goal is opening their minds to future possibilities, not to debate what the future actually can be (natural consequences will take care of that). Here is my method:

1) Find books and tons of photos that show a ton of details. I use books, flash cards, random photos, even advertisement photos.

2) Bring out their favorite game and lay the photos beside the game.

3) At this level, the child already knows the expectations.

4) Start the game. The first player looks at the picture and describes what she sees. This is important because this gives the story as they see it. It’s concrete, so use concrete language like “the people are in the boat”, “the dog is in the water”, or “the waves are huge”.

5) All the players look at the picture, then agree or disagree with the player’s description.

6) The player then says what the possible future may be. Using the language, “I think the waves will push the boat over”, “I think they will rescue the dog”, or “I think the people in the boat will be beamed up by aliens”. It doesn’t matter what the child says. The goal is not to correct the child’s idea of the future. The goal is to have the child be flexible in their thinking. If it’s dark, you can leave it, or have your version of the future when it’s your turn. Do NOT correct the child during their turn. It’s their turn and you can damage the relationship if you are constantly correcting the child on their turn. Save that for another goal, at another time.

7) When the child is finished predicting, the turn is over and they take their turn playing the game. Often by this level, the interest can be more into the predicting than playing the game. If the child wants to go on and on with their predictions, let them because the game is not the goal. This does not go on for hours. Whenever you choose to teach a target, you choose the system and how long it will last. You can set the expectation as an open ended game, which is with a timer, or closed ended one, which is with the number of turns.

8) I alternate between the open and closed ended. We seldom ever finish the game at this level, which is not a big deal.

9) Never let the game go for more than ten minutes for the very young, and fifteen for the older children. Put on the timer, and when it goes off, you say, “Do you want the game to be over?” or “Do you want to play for another ten or fifteen minutes?”.

10) If they choose game over, you can smile and say it was a fun game. If they choose to play, set the timer. If they want more, you tell them that you will play it at the next session, and then keep your word.

This is the end of sharing how I teach 5-W-H questions. In the future, I will share the different approaches I take. The system always stays the same, but the approach and materials change. As I said in earlier posts, I’m not a therapist or have formal education in teaching. I am a mom for thirty-one years and have lots of experience with children from parenting and running a private day home for twenty years. I was also a nanny in between and during doing those jobs. I have also been a child development facilitator for five years. I hope you enjoyed my posts, and found at least one tip to help you teach the 5-W-H questions!

Teaching the 5-W-H Questions: Part 3

By Christine Marchant

If you read my previous posts, you’d notice that I have a system to teaching the 5-W-H questions.

By the time the child has surpassed level two and is ready for level three, he is not impressed with the ‘preschool’ attempts. The magnetic fishing and the Caribou games no longer hold his interest. Using basic pictures will often bore him to death! There is no right or wrong way to teach, but the best way is to match your system to the child’s learning style. It is important to observe if the child is an active or passive learner. The active learner loves games and action. The passive learner prefers work sheets, scrabble and card games etc. I have watched many therapists teach the 5-W-H questions to children. Most of them are for younger children, I have had a few older children that are a bigger challenge. The little children are happy with ANY game you come up with, while the older ones are more tricky. With the older children, I find just saying: “this is our target—this is what we are doing and when we are finished, then you can play your game” is the more effective. We set up their favorite game, then we do “target” then your turn, “target” then your turn. My rules are that we do two cycles of “target’ games, then we do one game “free style” game. Free style is playing the game any way the child wants to. It’s ok if the child rigs it for them to win EVERY TIME! I don’t care! Just get the child hooked.

Teaching before and after is often a challenge. It’s vague and abstract thinking. It’s been proven that we can envision the past easier than the future. That’s why I teach “before” first.

1) Find books or photos that show a TON of details in each photo. I use books, flash cards, and random photos saved on to my Ipad.

2) I bring out their favorite game, then the photos.

3) At this level, the child is already hooked into the program. The first player looks at the photo, and describes what is in the photo, then says what he thinks might have happened just before this photo.

4) The other players can agree or disagree. This opens an interesting conversation.

5) Follow the same pattern that I shared in the previous posts:

What do you suppose happened before the girl fell off her bike?

Who do you suppose she was with?

Why do you suppose she fall off the bike?

Where do you suppose she was?

When do you suppose this happened?

How did we come up with the “before” information?

6) When all players are satisfied with the answers, the player takes their turn.

7) By providing their favorite game, the child is usually motivated to do the “work”.

8) Sometimes, at this level, the child finds it difficult and tries to avoid the “work”. If this happens, just sit quiet and say, first we do the “target” then you can play the game. The desire to play usually is enough.

I find it very rewarding to see the children go on this journey. I love seeing the look of amazement and understanding in their eyes as they become more aware of their world. I decided in high school that I wanted to work with children and I’ve enjoyed every year. I have one more post on this topic, which involves teaching “after” and then I move on to teaching other aspects of language.

Teaching the 5-W-H questions: Part 1

By Christine Marchant

Teaching the 5-W-H questions (who, what where why and how) is different for each child. At least, that’s what I thought, until one day I realized that I’ve been teaching it for several years. I discovered that the verbal level of the child does not matter. I have a child who is not much higher than “non verbal.” She is very intelligent, but is unable to express herself. Without realizing it, I actually taught her the 5-W-H questions. I sat down and started to write down the formula I used. I then tried it on my preschool boy, and he got it! I then tried it on my other preschool boy and he got it! I was amazed! I wrote out the formula step by step, and next week, I will try it on my older boy.

I’m not a speech pathologist, but I do have decades of experience raising children, and 5 years experience as a child development facilitator. I am on many full service teams. I am only sharing my experience working with many therapists and children. This is the formula that works for me.

The 5-W-H questions can be very difficult to teach because they are abstract and can be a challenge for children and their support aides. I started with the most concrete and easy W question, and then worked up to the most abstract and difficult questions, which are WHY and HOW. Children will move through these steps at different speeds. The amount of time isn’t the goal. The goal is to have the child concretely understand the question and why and when to use it. Stay with the formula and repeat as often as needed. If the child ‘loses their grasp’ of the knowledge, just drop back one step, do a quick review, and when it’s concrete again move to the next step. Don’t change the order or the formula. Just go forward and backwards.

My girl took 3 years, my preschool boys took weeks, and my older boy will most likely have it mastered in a few sessions. Go slow and stay faithful to the formula. Do not move to the next level until the previous levels are set, concrete, and consistent. Once the child knows the formula, you don’t need the visual. I use the visual for my girl because she’s still almost non verbal and LOVES to print her thoughts. The visual helps her remember where each answer belongs. Once the child is consistently responding correctly to each question, you can mix them up and be creative.

On a sheet of paper, create 6 columns and in each column, print the 5-W-H questions allow enough space to print at least 4-5 words.

___________________________________________________________________

WHO WHAT WHERE WHEN WHY HOW

___________________________________________________________________

I like to use a set of 24 photos. Use 6 at a time- 3 turns each. I keep it to 10 to 15 minutes per activity.

I repeat the activity twice. Then put it away, I do this twice a session. It’s more effective to teach shorter lengths of time more often than longer times, less often.

Leave the columns blank and laminate the sheet.

Level 1

- Only ask WHO and leave the rest of the columns blank

- WHO is riding the bike?

- Do this for each photo, the adult should go first to model the correct response.

- Take turns until the 6 photos are done.

- Stay on this level until the child is consistently responding correctly

Level 2

- Only ask WHO-WHAT and leave the rest blank

- Do this for each photo, and the adult should go first to model the correct response.

- Take turns until the 6 photos are done.

- Stay on this level until the child is consistently responding correctly.

- WHO is riding the bike?

- WHAT is the boy doing?

Level 3

- Only ask WHO-WHAT-WHERE and leave the rest blank

- Do this for each photo, yougo first to model the correct response.

- Take turns until the 6 photos are done.

- Stay on this level until the child is consistently responding correctly

- WHO is riding the bike?

- What is the boy doing?

- WHERE are they riding the bike?

- Follow the same steps as level 1 and 2

Level 4

- Only ask WHO-WHAT-WHERE-WHEN

- WHO is riding the bike?

- WHAT is the boy doing?

- WHERE are they riding the bike?

- WHEN are they riding the bike?

- Repeat the same steps.

Level 5

- Only ask WHO-WHAT-WHERE-WHEN-WHY

- WHO is riding the bike?

- WHAT is the boy doing?

- WHERE are they riding the bike?

- WHEN are they riding the bike?

- WHY are they riding the bike?

- Follow the same steps

Level 6

- Only ask WHO-WHAT-WHERE-WHEN-HOW.

- WHO is riding the bike?

- WHAT is the boy doing?

- WHERE are they riding the bike?

- WHEN are they riding the bike?

- WHY are they riding the bike?

- HOW are they riding the bike?

- Repeat the same steps.

The Real Life Experience of Sensory Processing Disorder

By Alyssa Neudorf

The first question most people ask is, what is sensory processing disorder (SPD)? I would describe it simply as processing the entire world differently. A person who is partially sighted or hearing impaired will process the information coming to those senses in a different way from someone with typical vision or hearing.

What does this mean for me? As a person with SPD, it means that I process all the information coming to ALL of my senses differently, more intensely and all at the same time. Most people have the luxury of blocking out repetitive stimuli like the clock ticking, the clothes you are wearing, the smells in the air and, the chair you are sitting on while reading – this is not something I get to do. I am aware of everything all the time.

When all this intense and repetitive information becomes too much something called sensory overload is reached. Sensory overload can look and feel different for each individual person. For me, it is something that happens suddenly. I am fine until I am not. I begin to feel very warm, shaky, things start to dim around the outside of my eyes. My brain starts to try and leave my body making it very, very hard to speak or move without help. It feels like there is a tonne of bricks stacked on my vocal cords and the signals to legs are slow or blocked. Mentally I know I can speak and I can move but making that happen is very hard. It is at this point that a simple question, touch or surprise will trigger a meltdown. People will often ask “what do you need?”, or “what can I do?” The problem is at this point I don’t know and if I do I can’t always tell you. I can’t think and I feel frozen and stuck with everything spinning, flashing and pounding away around me all while becoming more intense. Then hyperventilation kicks in.

Sound exhausting and painful yet?

Having a schedule and routine helps me to plan out my sensory energy for the day. There is only such much I can do with 20 tokens and everything in your days takes different amounts. Getting dressed, eating, school, being social, going outside, tying your shoes, and taking the bus just to name a few. As a result, I can’t drive yet even though I would like to, don’t go shopping much, I wear certain clothing, most of my shoes don’t have laces (those that still do will be replaced with elastics), and I only wear specific socks. Clothes shopping is a big challenge and thus is avoided and is only done on a day when I don’t have to do anything else that day.

That is just a small window into the life of one person with SPD. It is different from person to person. Hopefully this article has helped you gain some understanding of what it is like to have SPD.

Connecting with a Multidisciplinary Approach

By: Stephanie Magnussen

Although it may seem apparent that a child needs specific help, there usually are many layers to an individual’s needs. For example, if a child has a speech delay, the parent may request that he sees a speech pathologist. But why does this child have a speech delay? Is there is a sensory need that is not being met, or are there developmental delays or behavioral issues at work? Kids are complicated little people, and it’s important to remember that what we see is only the tip of the iceberg. It’s really beneficial for a group of therapists to explore what lies beneath the surface to give the child the most effective strategies to thrive academically, socially, and mentally.

Perhaps the short term goals for a child with Autism Spectrum Disorder are maintaining eye contact and increased vocabulary, and the long term goals are independence and integration into a typical classroom. The speech pathologist will develop activities that increase vocabulary, while the occupational therapist creates drills for promoting eye contact, and the psychologist may make social stories that build confidence and promote more appropriate social behavior. Just having one therapist would not be the most advantageous for the child and family in this case. The parents are also part of the multidisciplinary team. They must be on board with practicing what the therapists are working on and provide a supportive environment for the child to thrive under this team approach.

At Connecting Dots, all of the therapists are registered health care professionals with Master’s level education. They all work together and share ideas on how to set a child up for success by using each of their expertise. If a child is exhibiting disfluent speech or a stutter, and therefore struggling socially at school, of course we want to promote smooth speech, but there may be other issues to address. The child may have motor planning deficits which result in disfluent speech. The speech pathologist can work on an action plan for smooth speech, while the occupational therapist develops a plan to promote increased ability for the muscles to make the correct movements for speech. Psychologists are also a key part of this multidisciplinary approach. Communication is not just the words that we speak, but also our ability to interact with those around us. Any disability can be stressful for a child, and may result in anxiety and social isolation. A psychologist can identify activities and games that will help a child excel socially.

As an aide at Connecting Dots, I have been fortunate to work with speech pathologists, occupational therapists, and psychologists and have seen the gains my clients are making by working on each piece of their puzzle. Every child’s background and needs are so diverse, and an individualized plan with input from different types of therapists allows the team to work on gains for the child in a holistic manner. It is truly a team approach between the therapists, aides, and family members.